アルコール飲料は、国際がん研究機関(IARC)によってグループ1の発がん物質(ヒトに対する発がん性)として分類されています。 IARCは、女性の乳がん、結腸直腸がん、喉頭がん、肝臓がん、食道がん、口腔がん、咽頭がんの原因としてアルコール飲料の摂取を分類しています。 [2]

全世界のがん症例の3.6%およびがんによる死亡の3.5%がアルコールの摂取に起因しています(正式にはエタノールとも呼ばれます)。 [4][5]

一部の国では、アルコールと癌について消費者に知らせるアルコール包装の警告メッセージを導入しています。[6]

アルコール業界は、アルコール摂取による癌のリスクについて一般の人々に積極的に誤解させようとしました。アルコール関連の癌による死亡率 [ edit ]

オーストラリア:2009年の研究で、アルコール飲料に癌警告ラベルを貼ることを義務付ける法律の撤廃のキャンペーンが追加された。 [9]

ヨーロッパ:2011年の調査では、男性の全がんの10分の1、女性の33人に1人が過去または現在のアルコール摂取によるものであることがわかった。[1965]発がん物質としてのアルコールと共発癌物質 編集 世界保健機関(WHO)の国際癌研究機関(International De Recherche surre Cancer)は、アルコールをグループとして分類しています。発ガン性物質、ヒ素、ベンゼン、アスベストに類似。その評価は、「ヒトにおけるアルコール飲料の発がん性についての十分な証拠がある。…アルコール飲料は、いかなる量でもヒトに対して発がん性がある(グループ1)」と述べている。[12] アセトアルデヒドは、エタノールを分解するので肝臓から産生されます。その後肝臓は通常99%のアセトアルデヒドを除去します。平均的な肝臓は1時間に7グラムのエタノールを処理することができます。例えば、ワイン1本中のエタノールを除去するのに12時間かかり、12時間以上のアセトアルデヒド曝露を与えます。 レビューで、Pöschland Seitz [15] 発がん物質としてのアルコールの考えられるメカニズム: Purohita 他重複リストを提案する: BoffettaとHashibeは以下のようなもっともらしいメカニズムを列挙している: 喫煙と飲酒の両方をする人は、口腔癌、気管癌、食道癌を発症するリスクがはるかに高いです。研究によると、これらの癌を発症するリスクは、喫煙も飲酒もしていない個人よりも35倍高いということです。この証拠は、アルコールとタバコ関連発がん物質との間に発がん性相互作用があることを示唆している可能性がある。メカニズム [ edit ]

アセトアルデヒド [編集]

アルコールデヒドロゲナーゼの遺伝子の欠損により、通常よりも多くのアセトアルデヒドにさらされている人が、上部消化管がんと肝臓がんを発症するリスクが高いことを、818人の大量飲酒者を対象とした研究で明らかにしました。飲酒とさまざまな種類の癌。 2009年のデータによると、米国では癌による死亡の3.5%がアルコールの消費によるものでした[14] edit

アルコールの局所的影響アセトアルデヒドへの代謝(生理学的に意味のあるレベルで変異原性がある可能性がある)

弱い変異原性および発がん性物質であるアセトアルデヒドの産生

アセトアルデヒドの遺伝毒性作用

アルコール摂取に伴う癌のリスクは口腔、咽頭、食道など、アルコールの摂取により最も接触している組織の方が高い。これは、エタノールが証明された変異原であり、さらに、肝臓で産生されるエタノールの代謝産物(アセトアルデヒド)が非常に発がん性であるという事実によって説明され、したがって局所(口腔、喉、食道癌)と遠方(皮膚、肝臓)の両方を説明する(乳房)がん。エタノールがアルコール飲料中に存在する濃度で細胞死を引き起こすことはよく知られている。生存している細胞が発がんに至るゲノム変化を起こす可能性がある細胞培養では、5〜10%エタノールへの1時間の曝露または30〜40%エタノールへの15秒間の曝露で生存する細胞はほとんどありません。しかし最近の証拠は、口腔、咽頭および食道を裏打ちする細胞に対するエタノールの細胞傷害作用が、死んだ細胞を置き換えるために粘膜のより深い層に位置する幹細胞の分裂を活性化することを示唆している。幹細胞が分裂するたびに、それらは細胞分裂に関連する避けられないエラー(例えば、DNA複製中に起こる突然変異および有糸分裂中に起こる染色体変化)にさらされるようになり、またDNA損傷剤の遺伝毒性活性に対して非常に脆弱になる。たばこ発がん性物質)アルコール摂取はおそらく、これらの組織を恒常性に維持する幹細胞における細胞分裂の蓄積を促進することによって、口腔、咽頭、および食道の癌を発症するリスクを高めます。エタノールの細胞傷害活性は濃度依存的であるため、これらの癌のリスクはエタノールの量が増えると増加するだけでなく、濃度が増加するとも増加します。 1オンスのウイスキーは、ノンアルコール飲料と混合して摂取するよりも、希釈せずに摂取するとおそらくより発がん性があります。エタノールの局所的な細胞傷害性効果は、これらの癌のリスクに対するアルコールとタバコの使用の既知の相乗効果も説明している可能性がある[21]

[編集]

[22][23]

アルコールが上皮間葉転換(EMT)を刺激すると、通常の癌細胞はより攻撃的な形態に変化し、全身に広がり始めます [ ] edit ]

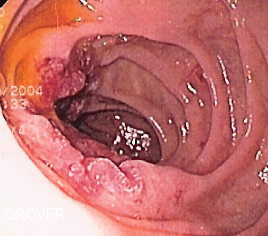

C型肝硬変患者における肝細胞癌(HCC)の腫瘍増殖に対するアルコール摂取の影響に関する研究は、アルコールが腫瘍体積倍加時間(TVDT)に影響を与えることを見出した。[24]

[25] マウスを用いた2006年の研究では、中等度の飲酒がより大きくより強い腫瘍をもたらすことが示されました。 [26][27]

大量のアルコールをマウスに投与した研究では、体脂肪の減少と免疫活性の低下によって癌の増殖が促進されることが示唆されています。 [ edit ]

ある研究では、「ADH1C * 1対立遺伝子および遺伝子型ADH1C * 1/1はアルコール関連癌患者で有意に多かった」[29] [30] アルコールはポルフィリノゲン性化学物質として知られています。いくつかのヨーロッパの研究は、遺伝性の肝性ポルフィリン症を肝細胞癌に対する素因と結び付けました。 HCCの典型的な危険因子は、急性肝性ポルフィリン症、特に急性間欠性ポルフィリン症、多様体ポルフィリン症および遺伝性コプロポルフィリン症に存在する必要はない。 Porphyria cutanea tardaもHCCに関連していますが、肝向性ウイルス、ヘモクロマトーシスおよびアルコール性肝硬変の証拠を含む典型的な危険因子と関連しています。ヘム代謝経路の2番目の酵素に影響を及ぼすチロシン代謝の遺伝性疾患であるI型チロシン血症は、子供を含むより若い集団でHCCを発症するリスクが高いことに関連している。 [ edit ] edit ] 女性での摂取は、口腔がん、咽頭がん、食道がん、喉頭がん、直腸がん、乳がん、肝臓がんのリスク増加と関連があると判断されました。[31] アルコールの摂取量は、口、癌、咽頭、喉頭のがんの危険因子です。米国国立癌研究所は、「飲酒は男性と女性の口、食道、咽頭、喉頭、そして肝臓の癌のリスクを増大させます。…一般に、リスクはベースラインを超えてアルコール摂取を伴うと増大します。 1週間に7杯以上のワインを飲んでいる人では、中程度のアルコール摂取量(1日に1杯のワイン)でリスクが最も高くなります(飲み物は通常のビール12オンス、5オンスのワインと定義されます)。また、タバコと一緒にアルコールを使用する方が、口、のど、および食道のがんになる可能性がさらに高まるため、どちらか一方を単独で使用するよりも危険です。」[32] 政府の「アメリカ人の食事ガイドライン」2010では、中程度の飲酒量を女性で1日1回まで、男性で1日2回までと定義しています。大量飲酒は、1日に3回以上、女性は1週間に7回以上、男性は1日に14回以上の飲酒と定義されています。 国際頭頸部癌疫学(INHANCE)コンソーシアムは、この問題に関するメタ研究を調整した。[33] このように、喉頭癌と飲料の種類を調べた研究では、この研究はイタリア人集団において特徴付けられるワインを頻繁に摂取すると、ワインは喉頭がんのリスクに最も強く関連する飲料です。」 [34] 1966年から2006年までに発表された疫学文献のレビューは次のように結論した:中等度の摂取でリスクが増大する

口腔がん、食道がん、咽頭がん、喉頭がん ] [ edit ]

1日に定期的に飲まれる追加の飲物のすべてについて、口腔内での発生率が高いとの結論が出ています。食道がんおよび喉頭がんの発生率は1000あたり0.7ずつ増加しています。 [31]

2008年の研究では、アセトアルデヒド(アルコールの分解生成物)が口腔がんに関係していることが示唆されています。[37][38]

[111]

アルコールは乳がんの危険因子です。 [39] [151] [1945989] [42] [1945991] [43] [43]

1日に平均2単位のアルコールを飲む女性は、1日に平均1単位のアルコールを飲む女性よりも、乳がんを発症するリスクが8%高くなります。 1日に定期的に飲酒すると、1000人に11人の割合で乳がんの発生率が上昇します。[31] 英国で報告された乳がんの約6%(3.2%から8.8%)は、飲酒が非常に少なくなると予防できます。低レベル(すなわち、1単位/週未満)[44] 中程度から大量のアルコール飲料の摂取(1週間に少なくとも3から4回の飲酒)は、乳がんの再発リスクが1.3倍になることに関連しています。さらに、任意の量のアルコールの摂取は、乳がんの生存者における再発リスクの有意な増加と関連しています。 [ edit ]

飲酒は、早期発症の原因となり得る。大腸がん[47] アルコールが腸がんの原因であるという証拠は、男性には説得力があり、女性には確からしいです。 [48]

国立衛生研究所、[49] 国立癌研究所、[50] 癌研究、[51] アメリカ癌学会、[52] メイヨークリニック、[53] 、および結腸直腸癌連合[54] 米国臨床腫瘍学会[55] およびMemorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center [56] は危険因子としてアルコールを挙げている。

WCRFのパネルレポートは、アルコール飲料が1日30グラムを超える絶対アルコールの摂取レベルで男性の大腸がんのリスクを増加させるという「説得力のある」証拠を見出している[57] 。大腸がんのリスクを高める」 [58]

2011年のメタアナリシスにより、アルコール摂取は大腸がんのリスク増加と関連していることが明らかにされた。[59]

編集

アルコールは、肝硬変による肝癌の危険因子です。[60][61][62] 肝硬変は、最も一般的には慢性的なアルコールの使用による、肝臓内の瘢痕形成に起因します。 [63]

「肝硬変患者の約5%が肝癌を発症している。肝硬変はアルコール乱用による損傷後に肝細胞が瘢痕組織に置換されると発症する疾患である」… [64]

NIAAAは、「長時間の大量飲酒は多くの場合原発性肝癌と関連している」と報告している。しかし、アルコールによるものか別の要因によるものかにかかわらず、肝硬変が癌を誘発すると考えられています。」 [65] [66]

「1日に5回以上飲酒すると、肝癌が発生する可能性が著しく増加します」(NCI)。

ある研究では、1日に定期的に摂取される追加の飲み物ごとに、肝がんの発生率が1000人あたり0.7人増加すると結論しています。 [31]

米国では、肝癌は比較的まれであり、10万人あたり約2人が罹患しているが、過剰なアルコール摂取は、一部の研究者らによってこれらの症例の36%ほどに関連している。 HCVによるもの[hepatitis C virus]、HBVによるもの[hepatitis B virus]、および18%のアルコール依存症の飲酒。[68] イタリア北部のブレシア県での研究は、「人口寄与リスク(AR)に基づく」と結論づけている。大量のアルコール摂取がこの領域におけるHCCの最も関連性の高い原因であると思われ(AR:45%)、続いてHCV(AR:36%)、およびHBV(AR:22%)感染である。」[69]

[ edit 1日に2杯以上のアルコールを摂取することは、肺がんのリスクがわずかに増加することと関連しています[70] Freudenheimによる研究へのコメント他。 、R. Curtis Ellison MDは、次のように述べています。 [71]

皮膚がん [編集]

アルコール摂取は、悪性黒色腫の発症と関連しています。[72]

胃がん[73]

] [

edit ]

] [

edit ]「胃がん、結腸、直腸、肝臓、女性の乳房、および卵巣のがんについても統計的に有意なリスクの増加が存在した。」 [73]

"アルコールは胃がんの原因として広く研究されてきましたが、それがリスクを高めるという決定的な証拠はありません。しかし、少なくとも3つの研究からの結果はヘビー喫煙者の胃がんのリスクを高めるかもしれないことを示唆します。 " [74] [75] [76] [77]

台湾の研究では、「…タバコの喫煙は胃がんの初期発症において最も有害な役割を果たす可能性があり、アルコールを飲むことでプロセスが促進される可能性がある」と結論づけられている。 [74]

ノルウェーの研究によると、「アルコールへの曝露の程度と胃がんのリスクとの間に統計的に有意な関連は明らかにされていないが、タバコの高使用量(20日以上)とアルコールの組み合わせ(14日以上) 1日当たり50g以上の摂取はリスクを増大させる [ edit ])非心臓性胃がんのリスクを非使用者と比較してほぼ5倍増加させた(HR = 4.90 [95% CI = 1.90–12.62])。

子宮内膜がん 編集

アルコールが胆嚢癌の危険因子として示唆されている。アルコールの高摂取は胆嚢に関連していることが証拠から示唆されている。 [84][85] 男性は女性よりアルコール関連胆嚢がんのリスクが高い可能性がある。[86]

卵巣がん 編集]

その比較的高い[87] 「アルコール摂取と卵巣癌および前立腺癌との間にも関連性が認められたが、50人に1人のみであった。 "[88]

"胃、結腸、直腸、肝臓、女性の乳房、および卵巣のがんについても、統計的に有意なリスクの増加が認められた。 [73]

[したがって、このプール分析は、中等度のアルコール摂取と卵巣癌リスクとの間の関連性を支持するものではない。] [89]

前立腺癌 [編集]

医療従事者追跡調査では、全体的なアルコール摂取と前立腺がんリスクとの間には弱い関連しか示されず、赤ワイン摂取と前立腺がんリスクとの間には関連性がまったく示されていませんでした。」[90] [

2001年に発表されたメタアナリシスでは、男性が50 g /日を超えるアルコールを飲む場合の小さいながらも有意に高いリスクが見られ、男性が100 g /日を超えるアルコールを飲む場合のリスクがわずかに高かった。アメリカでのコホート研究では、適度な量のスピリッツを飲んでいる男性や、大酒飲みの飲酒者のリスクが高いことがわかっています[92] 、ビールやワインの適度な摂取はリスクの増加とは関連していません。 ] [94] [95]

1日当たり50 gおよび100 gのアルコール摂取も卵巣がんおよび前立腺がんに関連する[88] しかし、ある研究では、中程度のアルコール摂取は前立腺がんのリスクを高めると結論付けられている。酒や酒ではなく、酒の消費は前立腺癌と正の関連がありました。 [93]

フレッドハッチンソンがん研究センターは、1週間に4杯以上の赤ワインを摂取した男性の前立腺がん発症リスクが50%減少したことを発見しました。彼らは、「ビールや酒類の消費に関連した重大な影響(プラスもマイナスも)も、白ワインとの一貫したリスク低減も見いだせなかった。これは、他の種類のアルコールが欠けている有益な化合物が赤ワインになければならないことを示唆する。 …赤ぶどうの皮に豊富に含まれるレスベラトロールと呼ばれる抗酸化物質であるかもしれません。」 [94] [96]

2009年に発表された研究のメタアナリシスは、1日に2標準飲料だけを摂取すると、癌リスクが20%上昇することを発見しました。[97][98]

[ edit ]

小腸がん患者の研究では、飲酒が腺がんおよび悪性カルチノイド腫瘍と関連していることが報告されている。 [99] [99]

「男性と女性を合わせた場合、飲酒量が多い場合(80±gエタノール/日)のリスクが、中等度よりも3倍有意に高かった。

飲酒者および非飲酒者が観察された。 [100]

「アルコールとタバコの消費は小腸の腺癌のリスクを増大させなかった。…現在のデータはタバコまたはアルコールの主な影響と矛盾しているが、これらの要因と小腸癌との間の中程度の関連は不明瞭である[101]

証拠が混在している [編集

白血病 [編集]

妊娠中のアルコールの摂取はあった[102] 国立癌研究所が発表したレビューでは、妊娠中の母親のアルコール摂取は「示唆的」なカテゴリーに分類されていたが、リスクは重要ではないと結論づけられている。[103]

- 急性リンパ性白血病(ALL)

]小児のALLでは、妊娠中の母親のアルコール摂取は「ALLの重要な危険因子となる可能性は低い」[103]

- 急性骨髄性白血病(AML)

結論として、我々の研究では明らかにされなかったアルコール摂取と白血病リスクとの明確な関連、リスク推定のパターンのいくつか(アルコール摂取とALL、AML、およびCLLリスクとの間の可能なJ字型用量反応曲線、およびアルコールとCMLとの間の正の関連) [104]

- 小児AML

3つの研究で、妊娠中にアルコール飲料を飲んでいた母親のリスク増加(約1.5〜2倍)が報告されています。 [103] 「妊娠中の母親のアルコール摂取は、乳児白血病、特にAMLのリスクを増大させる」[105]

- 急性非リンパ球性白血病(ANLL)[105]

- 研究は、アルコール摂取の間に明確な関連性が示されていないにもかかわらず、アルコールへの子宮内曝露が小児期ANLLのリスクを2倍にしたことを発見した。そして、白血病リスク、リスク推定のパターンのいくつか(アルコール摂取とALL、AML、およびCLLリスクとの間の可能なJ字型用量反応曲線、およびアルコールとCMLの間の積極的な関連性)は示唆的かもしれない。 [104]

- 慢性骨髄性白血病(CML)

- ある研究の結論は「なかった」ある喫煙は、喫煙、アルコールまたはコーヒーの摂取、有毛細胞白血病で発見された。[107]

多発性骨髄腫(MM) [ edit ]

多発性骨髄腫の原因としてアルコールが示唆されている。 、[108] ある研究では、飲酒者と非飲酒者との間の比較研究においてMMの間に関連性は見られなかったが、[109]

編集]

膵炎は十分に確立されており、アルコール摂取と膵臓癌との関連はあまり明らかではありません。全体的な証拠は、慢性的な大量のアルコール摂取に伴う膵臓がんのリスクのわずかな増加を示唆していますが、関連性がないことを示す多くの研究と矛盾するままです[110][111] 、1日最大30gのアルコールを摂取するリスクの増加 ] [112]

全体的に見て、関連性は一貫して弱く、ほとんどの研究で関連性は認められていません[19][112][113] アルコールを過剰に飲むことは慢性膵炎の主な原因です。 [114] 他の種類の慢性膵炎よりも膵臓癌の前駆体の頻度が低い

[1965976]アルコール摂取量の増加に伴ってリスクが増加するという関係が示唆された研究[116][117] [116][117] リスクは主に1日に4杯以上の飲酒で[119] 。 ] 1日に最大30gのアルコールを飲んでいる人にリスクが増大することはないようです[112][120][121] 、これは1日に約2アルコール飲料です[121] 。 [111] プールされた分析は、「我々の調査結果は、1日当たり30グラム以上のアルコールを摂取することによる膵臓がんのリスクの緩やかな増加と一致している」と結論付けた。 [121] [121]いくつかの研究は、それらの発見は交絡因子によるものである可能性があると警告している[110][122] リンクが存在するとしても、それは「アルコールそれ自体以外のアルコール飲料の内容による」[123] 。あるオランダの研究では、白ワインを飲む人の方がリスクが低いことがわかっています。 [124]

"慢性膵炎の10症例のうち約7症例は長期大量飲酒によるものです。慢性膵炎は膵臓がんの危険因子として知られています。しかしアルコールによる慢性膵炎はそれほどリスクを増大させません他の種類の慢性膵炎。アルコールと膵臓癌のリスクとの関連がある場合、それはごくわずかです。」 [114]

「我々の調査結果によれば、米国の一般集団が通常消費するレベルの飲酒は、おそらく膵臓がんの危険因子ではないということです。しかし、大量の飲酒は膵臓がんリスクに関連する可能性があります。 " [111]

「膵臓がんの相対リスクは、年齢、喫煙状況、およびたばこ数年の喫煙を調整した後の飲酒量(Ptrend = 0.11)に伴って増加した。」 [125]

「アルコール依存症の膵臓がんのリスクは40%程度しかないが…アルコール依存症患者における膵臓がんの過剰リスクは小さく、喫煙による交絡が原因であると考えられる。」 [110]

「膵臓がんの相対リスクは、脂肪とアルコールの摂取量とともに増加することが示されました。アルコールは、膵臓がんの病因に直接関与していない可能性があります。飲料 [126]

"酒を飲んでいない人からのデータと比較すると、エタノール、ビール、スピリッツ、赤ワイン、強化ワインのグラム数で表した全種類のアルコールの累積生涯消費量はリスクとは無関係であった。リスクを伴う…。白ワインの生涯の飲み物の数のための一様に減少したリスク推定値は少数に基づいていた…。」 [127]

「ほとんどの場合、総アルコール、ワイン、酒、ビールの摂取量は膵臓癌と関連していなかった。」 [128]

「これら2つの大規模コホートからのデータは、コーヒー摂取量またはアルコール摂取量と膵臓癌リスクとの間の全体的な関連性を支持するものではない」 [112]

「我々の調査結果は、1日当たり30グラム以上のアルコールを摂取することによる膵臓がんのリスクのわずかな増加と一致している。] [1]

慢性リンパ性白血病(CLL)[104]

イタリアでの集団ベースの症例対照研究では、飲酒とCMLの間に有意でない正の関連が見出された。[104]

[ edit

このセクションでは、アルコールが危険因子として挙げられていない癌、および論文が発表されている癌を列挙している。

小児星細胞腫編集

アルコールへの胎児曝露は小児星細胞腫と関連していないとの研究が結論されています[130]

編集[130]

]

文献のレビューにより、アルコール使用と胆管がんの間に関連性はないことが判明した。[131]

膀胱がん [編集]

「アルコールに関する疫学データ両方の習慣について、いくつかの調査で観察されたリスクの緩やかな増加の説明は、喫煙による残留交絡、またはアルコールとコーヒーの関連性に起因している可能性があります。 , and yet unidentified risk factors for bladder cancer."[132]

Cervical cancer[edit]

A study concluded "that alcoholic women are at high risk for in situ and invasive cervical cancer" but attributed this to indirect, lifestyle-related reasons.[133]

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) breast cancer[edit]

"DCIS patients and control subjects did not differ with respect to oral contraceptive use, hormone replacement therapy, alcohol consumption or smoking history, or breast self-examination. Associations for LCIS were similar."[134]

Ependymoma[edit]

A review of the basic literature[135] found that consumption of beer was associated with increased risk in one study[136] but not in another[137]

Intraocular and uveal melanomas[edit]

A study found no association between alcohol and uveal melanoma.[138]

Nasopharynageal cancer / Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC)[edit]

A systematic review found evidence that light drinking may decrease the risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma whereas high intake of alcohol may increase the risk.[139]

Neuroblastoma[edit]

A few studies have indicated an increased risk of neuroblastoma with use of alcohol during pregnancy.[140]

Salivary gland cancer (SGC)[edit]

Alcohol use is associated with an increased risk of salivary gland cancer.[19659257]Testicular cancer[edit]

A review concluded that "There is no firm evidence of a causal relation between behavior risks [tobacco, alcohol and diet] and testicular cancer."[142]

Thyroid cancer[edit]

A 2009 review found that alcohol intake does not affect the risk of developing thyroid cancer.[143] However, a 2009 study of 490,000 men and women concluded that alcohol may reduce the risk of thyroid cancer.[144] A 2009 study of 1,280,296 women in the United Kingdom concluded, "The decreased risk for thyroid cancer that we find to be associated with alcohol intake is consistent with results from some studies, although a meta-analysis of 10 case–control studies and two other cohort studies reported no statistically significant associations."[145]

Vaginal cancer[edit]

A Danish study found that "Abstinence from alcohol consumption was associated with low risk for both VV -SCCvagina and VV-SCCvulva in our study."[146]

A study concluded that alcoholic women are at high risk for cancer of the vagina.[133] In both studies, indirect, lifestyle-related reasons were cited.

Vulvar cancer[edit]

One study reported "No consistent association emerged between milk, meat, liver, alcohol and coffee consumption and risk of vulvar cancer."[147] A Danish study found the reverse, that alcohol consumption is significantly associated with VV-SCCvagina and VV-SCCvulva cancer.[146] A Swedish study concluded that alcoholic women are at no higher risk for cancer of the vulva.[133]

Might reduce risk[edit]

Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL)[edit]

A study concluded, "The results of this large-scale European study … suggested a protective effect of alcohol on development of NHL for men and in non-Mediterranean countries."[148] A population based case-control study in Germany found that alcohol reduced the risk of HL for both men and women but more so for men, whose risk was lowered by 53%.[149]

A population-based case-control study in Italy reported a protective effect of alcohol consumption on risk of HL among non-smokers.[109] Analysis of data from a series of case-control studies in Northern Italy revealed a modest positive effect of alcohol on lowering risk of HL among both smokers and non-smokers.[150]

Kidney cancer (Renal cell carcinoma) (RCC)[edit]

"Moderate alcohol consumption was associated with a lower risk of renal cell cancer among both women and men in this pooled analysis"[151] "This pooled analysis found an inverse association between alcohol drinking and RCC. Risks continued to decrease even above eight drinks per day (i.e. >100 g/day) of alcohol intake, with no apparent levelling in risk."[152]

A study concluded, "Results from our prospective cohort study of middle-aged and elderly women indicate that moderate alcohol consumption may be associated with decreased risk of RCC."[153] Researchers who conducted a study in Iowa reported that "In this population-based case-control investigation, we report further evidence that alcohol consumption decreases the risk of RCC among women but not among men. Our ability to show that the association remains after multivariate adjustment for several new confounding factors (i.e., diet, physical activity, and family history) strengthens support for a true association.[154]

Another study found no relationship between alcohol consumption and risk of kidney cancer among either men or women.[155]

A Finnish study concluded, "These data suggest that alcohol consumption is associated with decreased risk of RCC in male smokers. Because most of the risk reductions were seen at the highest quartile of alcohol intake and alcohol is a risk factor for a number of cancers particularly among smokers, these data should be interpreted with caution."[156] "Our data suggest an inverse association between alcohol intake and risk of renal cell cancer…"[157] Compared with nondrinkers, men who drank one or more drinks per day had a 31% lower risk of kidney cancer among 161,126 Hawaii-Los Angeles Multiethnic Cohort participants.[158]

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL)[edit]

A study concluded, "People who drink alcoholic beverages might have a lower risk of NHL than those who do not, and this risk might vary by NHL subtype."[159] "Compared with nondrinkers, alcohol consumers had a lower risk for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma overall … and for its main subtypes."[160] A study concluded, "Nonusers of alcohol had an elevated NHL risk compared with users…"[161]

Some studies have found a protective effect on NHL of drinking some forms of alcoholic beverage or in some demographic groups. A study of men in the US found that consumption of wine, but not beer or spirits, was associated with a reduced NHL risk[162] and a large European study found a protective effect of alcohol among men and in non-Mediterranean countries.."[163] A study of older women in Iowa found alcohol to reduce the risk of NHL and the amount of alcohol consumed, rather than the type of alcoholic beverages, appeared to be the main determinant in reducing risk."[164] A possible mechanism has been suggested.[165]

Some studies have not found a protective effect from drinking. British research found no association between frequency of drinking and NHL[166] and research in Sweden found that total beer, wine, or liquor intake was not associated with any major subtype of NHL examined, apart from an association between high wine consumption and increased risk of chronic lymphocytic leukemia.."[167]

One study of NHL patients concluded, "Our findings strongly encourage physicians to advise NHL patients to stop smoking and diminish alcohol consumption to obtain improvements in the course of NHL."[168]

Recommended maximum alcohol intake[edit]

As outlined above, there is no recommended alcohol intake with respect to cancer risk alone as it varies with each individual cancer. See Recommended maximum intake of alcoholic beverages for a list of governments' guidances on alcohol intake which, for a healthy man, range from 140–280g per week.

One meta-analysis suggests that risks of cancers may start below the recommended levels. "Risk increased significantly for drinkers, compared with non-drinkers, beginning at an intake of 25 g (< 2 standard drinks) per day for the following: cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx (relative risk, RR, 1.9), esophagus (RR 1.4), larynx (RR 1.4), breast (RR 1.3), liver (RR 1.2), colon (RR 1.1), and rectum (RR 1.1)"[169][170]

World Cancer Research Fund recommends that people aim to limit consumption to less than two drinks a day for a man and less than one drink a day for a woman. It defines a "drink" as containing about 10–15 grams of ethanol.[171]

Alcohol industry manipulation of the science on alcohol and cancer[edit]

A study published in 2017 has found that front organisations set up by the world's leading alcohol companies are actively misleading the public about the risk of cancer due to alcohol consumption. The study drew parallels with the long-standing activities of the tobacco industry. It also claimed that there was a particular focus on misleading women drinkers, because much of the misinformation about cancer produced by these companies was found to be focused on breast cancer.[7]

The alcohol industry around the world has also campaigned to remove laws that require alcoholic beverages to have cancer warning labels.[8]

References[edit]

- ^ Global Status Report on Alcohol 2004 (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2004. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-92-4-156272-0.

- ^ Cogliano, VJ; Baan, R; Straif, K; Grosse, Y; Lauby-Secretan, B; El Ghissassi, F; Bouvard, V; Benbrahim-Tallaa, L; Guha, N; Freeman, C; Galichet, L; Wild, CP (Dec 21, 2011). "Preventable exposures associated with human cancers". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 103 (24): 1827–39. doi:10.1093/jnci/djr483. PMC 3243677. PMID 22158127.

- ^ Boffetta P, Hashibe M, La Vecchia C, Zatonski W, Rehm J (August 2006). "The burden of cancer attributable to alcohol drinking". International Journal of Cancer. 119 (4): 884–7. doi:10.1002/ijc.21903. PMID 16557583.

- ^ Cheryl Platzman Weinstock (8 November 2017). "Alcohol Consumption Increases Risk of Breast and Other Cancers, Doctors Say". Scientific American. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

The ASCO statement, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, cautions that while the greatest risks are seen with heavy long-term use, even low alcohol consumption (defined as less than one drink per day) or moderate consumption (up to two drinks per day for men, and one drink per day for women because they absorb and metabolize it differently) can increase cancer risk. Among women, light drinkers have a four percent increased risk of breast cancer, while moderate drinkers have a 23 percent increased risk of the disease.

- ^ Noelle K. LoConte, Abenaa M. Brewster, Judith S. Kaur, Janette K. Merrill, and Anthony J. Alberg (7 November 2017). "Alcohol and Cancer: A Statement of the American Society of Clinical Oncology". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 36 (1).

Clearly, the greatest cancer risks are concentrated in the heavy and moderate drinker categories. Nevertheless, some cancer risk persists even at low levels of consumption. A meta-analysis that focused solely on cancer risks associated with drinking one drink or fewer per day observed that this level of alcohol consumption was still associated with some elevated risk for squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus (sRR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.09 to 1.56), oropharyngeal cancer (sRR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.06 to 1.29), and breast cancer (sRR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.08), but no discernable associations were seen for cancers of the colorectum, larynx, and liver.

CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Cancer warning labels to be included on alcohol in Ireland, minister confirms". Belfasttelegraph.co.uk. Belfast Telegraph. 26 September 2018.

- ^ a b Petticrew M, Maani Hessari N, Knai C, Weiderpass E, et al. (September 2017). "How alcohol industry organisations mislead the public about alcohol and cancer". Drug and Alcohol Review [Epub ahead of print]. 37 (3): 293–303. doi:10.1111/dar.12596. PMID 28881410.[1]

- ^ a b Chaudhuri, Saabira (9 February 2018). "Lawmakers, Alcohol Industry Tussle Over Cancer Labels on Booze". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Study bolsters alcohol-cancer link ABC News 24 August 2009

- ^ BBC Drinking over recommended limit 'raises cancer risk' 8 April 2011

- ^ Madlen Schütze et al. Alcohol attributable burden of incidence of cancer in eight European countries based on results from prospective cohort study BMJ 2011; 342:d1584 doi:10.1136/bmj.d1584

- ^ International Agency for Rescarch on Cancer, World Health Organization. (1988). Alcohol drinking (PDF). Lyon: World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer. ISBN 978-92-832-1244-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-26.CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link) p8

- ^ Homann N, Stickel F, König IR, et al. (2006). "Alcohol dehydrogenase 1C*1 allele is a genetic marker for alcohol-associated cancer in heavy drinkers". International Journal of Cancer. 118 (8): 1998–2002. doi:10.1002/ijc.21583. PMID 16287084. Archived from the original on 2012-12-18.

- ^ National Cancer Institute [2] 2.What is the evidence that alcohol drinking is a cause of cancer?

- ^ Pöschl G, Seitz HK (2004). "Alcohol and cancer". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 39 (3): 155–65. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agh057. PMID 15082451.

- ^ Theruvathu JA, Jaruga P, Nath RG, Dizdaroglu M, Brooks PJ (2005). "Polyamines stimulate the formation of mutagenic 1,N2-propanodeoxyguanosine adducts from acetaldehyde". Nucleic Acids Research. 33 (11): 3513–20. doi:10.1093/nar/gki661. PMC 1156964. PMID 15972793.

- ^ Purohit V, Khalsa J, Serrano J (April 2005). "Mechanisms of alcohol-associated cancers: introduction and summary of the symposium". Alcohol. 35 (3): 155–60. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.05.001. PMID 16054976.

- ^ Boffetta P, Hashibe M (February 2006). "Alcohol and cancer". The Lancet Oncology. 7 (2): 149–156. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70577-0. PMID 16455479.

- ^ a b c "Alcohol and Cancer". Alcohol Alert. 21. 1993.

- ^ Blot WJ, McLaughlin JK, Winn DM, et al. (1 June 1988). "Smoking and drinking in relation to oral and pharyngeal cancer". Cancer Research. 48 (11): 3282–7. PMID 3365707.

- ^ Lopez-Lazaro M (October 2016). "A local mechanism by which alcohol consumption causes cancer". Oral Oncology. 62: 149–152. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.10.001. hdl:11441/52478. PMID 27720397.

- ^ Rush University Medical Center Alcohol Activates Cellular Changes That Make Tumor Cells Spread 26 October 2009

- ^ Forsyth CB, Tang Y, Shaikh M, Zhang L, Keshavarzian A (January 2010). "Alcohol stimulates activation of Snail, epidermal growth factor receptor signaling, and biomarkers of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in colon and breast cancer cells". Alcohol. Clin.経験値Res. 34 (1): 19–31. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01061.x. PMC 3689303. PMID 19860811.

- ^ Matsuhashi T, Yamada N, Shinzawa H, Takahashi T (June 1996). "Effect of alcohol on tumor growth of hepatocellular carcinoma with type C cirrhosis". Internal Medicine. 35 (6): 443–8. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.35.443. PMID 8835593.

In conclusion we found that alcohol intake was closely related to the tumor growth of HCC in patients with type C cirrhosis.

- ^ Gu JW, Bailey AP, Sartin A, Makey I, Brady AL (January 2005). "Ethanol stimulates tumor progression and expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in chick embryos". Cancer. 103 (2): 422–31. doi:10.1002/cncr.20781. PMID 15597382.

- ^ "Equivalent Of 2–4 Drinks Daily Fuels Blood Vessel Growth, Encourages Cancer Tumors In Mice" (Press release). American Physiological Society. 3 April 2006. Archived from the original on 29 June 2006. Retrieved 26 June 2009.

- ^ Tan W, Bailey AP, Shparago M, et al. (August 2007). "Chronic alcohol consumption stimulates VEGF expression, tumor angiogenesis and progression of melanoma in mice". Cancer Biology & Therapy. 6 (8): 1211–7. doi:10.4161/cbt.6.8.4383. PMID 17660711.

- ^ Núñez NP, Carter PA, Meadows GG (May 2002). "Alcohol consumption promotes body weight loss in melanoma-bearing mice". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 26 (5): 617–26. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2002.tb02583.x. PMID 12045469.

- ^ Homann N, Stickel F, König IR, et al. (April 2006). "Alcohol dehydrogenase 1C*1 allele is a genetic marker for alcohol-associated cancer in heavy drinkers". International Journal of Cancer. 118 (8): 1998–2002. doi:10.1002/ijc.21583. PMID 16287084.

- ^ "Clues to alcohol cancer mystery". BBC News. 25 May 2008. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ a b c d Allen NE, Beral V, Casabonne D, et al. (March 2009). "Moderate alcohol intake and cancer incidence in women". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 101 (5): 296–305. doi:10.1093/jnci/djn514. PMID 19244173.

- ^ "Alcohol Consumption". Cancer Trends Progress Report – 2007 Update. National Cancer Institute. December 2007. Retrieved 29 June 2009.Template:Date=June 2015

- ^ "Research Projects: Pooled analysis investigating the effects of beer, wine and liquor consumption on the risk of head and neck cancers". The International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ Garavello W, Bosetti C, Gallus S, et al. (February 2006). "Type of alcoholic beverage and the risk of laryngeal cancer". European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 15 (1): 69–73. doi:10.1097/01.cej.0000186641.19872.04. PMID 16374233.

- ^ "Alcohol and cancer: is drinking the new smoking?" (Press release). Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. 26 September 2007. Archived from the original on 7 September 2008. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ "Alcohol And Cancer: Is Drinking The New Smoking?" (Press release). Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Science Daily. 28 September 2007. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ Warnakulasuriya S, Parkkila S, Nagao T, et al. (2007). "Demonstration of ethanol-induced protein adducts in oral leukoplakia (pre-cancer) and cancer". Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine. 37 (3): 157–165. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00605.x. PMID 18251940. Archived from the original on 2013-01-05.

- ^ Alcohol and oral cancer research breakthrough Archived 2 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "What Are the Risk Factors for Breast Cancer?". American Cancer Society. 31 May 2009. Archived from the original on 29 April 2009. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ "What You Need To Know About Breast Cancer". National Cancer Institute.

- ^ "Definite breast cancer risks". CancerHelp UK. Cancer Research UK. 2017-08-30.

- ^ "Guide to Breast Cancer" (PDF). American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008. p. 6. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ Room, R; Babor, T; Rehm, J (2005). "Alcohol and public health". The Lancet. 365 (9458): 519–30. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17870-2. PMC 2378965. PMID 15705462.

- ^ a b Non-Technical Summary Archived 24 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine Committee on Carcinogenicity of Chemicals in Food Consumer Products and the Environment (COC)

- ^ American Association for Cancer Research Alcohol Consumption Increases Risk of Breast Cancer Recurrence 10 December 2009 Archived 1 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ BBC Alcohol link to breast cancer recurrence 11 December 2009

- ^ Zisman AL, Nickolov A, Brand RE, Gorchow A, Roy HK (March 2006). "Associations between the age at diagnosis and location of colorectal cancer and the use of alcohol and tobacco: implications for screening". Archives of Internal Medicine. 166 (6): 629–34. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.6.629. PMID 16567601.

- ^ "Types of cancer". World Cancer Research Fund. Archived from the original on 9 June 2009. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ "Colorectal Cancer – Step 1: Find Out About Colorectal Cancer Risk". National Cancer Institute. Archived from the original on 22 April 2009. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ "Colorectal Cancer Prevention". National Cancer Institute. 7 May 2009. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ "Food types and bowel cancer". Cancer Research. 19 September 2008. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ "What Are the Risk Factors for Colorectal Cancer?". American Cancer Society. 18 May 2009. Archived from the original on 19 April 2008. Retrieved 26 June 2009.

- ^ "Colon Cancer: Risk factors". Mayo Clinic. 2 May 2008. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ "Assessing Your Risk for Colorectal Cancer". Colorectal Cancer Coalition. 9 January 2009. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ "alcohol". 3 November 2015.

- ^ Sloan-Kettering – Colorectal Cancer: Risk Reduction

- ^ World Cancer Research Fund; American Institute for Cancer Research (2007). Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective (PDF). Washington, D.C.: American Institute for Cancer Research. ISBN 978-0-9722522-2-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 29 June 2009.[page needed]

- ^ National Cancer Institute (NCI) Cancer Trends Progress Report Alcohol Consumption Archived 16 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fedirko, V.; Tramacere, I.; Bagnardi, V.; Rota, M.; Scotti, L.; Islami, F.; Negri, E.; Straif, K.; Romieu, I.; La Vecchia, C.; Boffetta, P.; Jenab, M. (9 February 2011). "Alcohol drinking and colorectal cancer risk: an overall and dose-response meta-analysis of published studies". Annals of Oncology. 22 (9): 1958–1972. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdq653. PMID 21307158.

- ^ Risk Factors

- ^ What Are the Risk Factors for Liver Cancer?

- ^ Risk Factors Archived 23 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Liver Cancer: The Basics

- ^ Liver Cancer Archived 28 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Takada, Akira; Shujiro Takase; Mikihiro Tsutsumi (1992). "Alcohol and Hepatic Carcinogenesis". In Raz Yirmiya and Anna N. Taylor. Alcohol, Immunity, and Cancer. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. pp. 187–209. ISBN 978-0-8493-5761-9.CS1 maint: Uses editors parameter (link)

- ^ Villa, Erica; Margherita Melegari; Federico Manenti (1992). "Alcohol, Viral Hepatitis, and Hepatocellular Carcinoma". In Ronald Ross Watson. Alcohol and cancer. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. pp. 151–165. ISBN 978-0-8493-7938-3.CS1 maint: Uses editors parameter (link)

- ^ Duffy, S.W., and Sharples, L.D. Alcohol and cancer risk. In: Duffy, J.L., ed. Alcohol and Illness: The Epidemiological Viewpoint. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1992. pp. 64–127.'

- ^ Franceschi S, Montella M, Polesel J, et al. (April 2006). "Hepatitis viruses, alcohol, and tobacco in the etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Italy". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 15 (4): 683–9. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0702. PMID 16614109.

- ^ Donato F, Tagger A, Chiesa R, et al. (September 1997). "Hepatitis B and C virus infection, alcohol drinking, and hepatocellular carcinoma: a case-control study in Italy. Brescia HCC Study". Hepatology. 26 (3): 579–84. doi:10.1002/hep.510260308. PMID 9303486.

- ^ Freudenheim JL, Ritz J, Smith-Warner SA, et al. (1 September 2005). "Alcohol consumption and risk of lung cancer: a pooled analysis of cohort studies". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 82 (3): 657–67. doi:10.1093/ajcn.82.3.657. PMID 16155281.

- ^ Boston University Alcohol Consumption and Lung Cancer: Are They Connected? Archived 20 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Millen AE, Tucker MA, Hartge P, et al. (1 June 2004). "Diet and melanoma in a case-control study". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 13 (6): 1042–51. PMID 15184262.

- ^ a b Bagnardi V, Blangiardo M, La Vecchia C, Corrao G (2001). "Alcohol consumption and the risk of cancer: a meta-analysis". Alcohol Research & Health. 25 (4): 263–70. PMID 11910703.

- ^ a b Chen MJ, Chiou YY, Wu DC, Wu SL (November 2000). "Lifestyle habits and gastric cancer in a hospital-based case-control study in Taiwan". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 95 (11): 3242–9. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03260.x. PMID 11095349.

- ^ Inoue M, Tajima K, Hirose K, Kuroishi T, Gao CM, Kitoh T (February 1994). "Life-style and subsite of gastric cancer—joint effect of smoking and drinking habits". International Journal of Cancer. 56 (4): 494–9. doi:10.1002/ijc.2910560407. PMID 8112885.

- ^ a b Sjödahl K, Lu Y, Nilsen TI, et al. (January 2007). "Smoking and alcohol drinking in relation to risk of gastric cancer: a population-based, prospective cohort study". International Journal of Cancer. 120 (1): 128–32. doi:10.1002/ijc.22157. PMID 17036324.

- ^ Stomach Cancer risk factors

- ^ Tinelli A, Vergara D, Martignago R, et al. (2008). "Hormonal carcinogenesis and socio-biological development factors in endometrial cancer: a clinical review". Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 87 (11): 1101–13. doi:10.1080/00016340802160079. PMID 18607816.

- ^ UK Department of Health Review of Alcohol: Association with Endometrial Cancer p8

- ^ Newcomb PA, Trentham-Dietz A, Storer BE (1997). "Alcohol consumption in relation to endometrial cancer risk". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 6 (10): 775–778. PMID 9332758.

- ^ Setiawan VW, Monroe KR, Goodman MT, Kolonel LN, Pike MC, Henderson BE (February 2008). "Alcohol consumption and endometrial cancer risk: The Multiethnic Cohort". International Journal of Cancer. 122 (3): 634–8. doi:10.1002/ijc.23072. PMC 2667794. PMID 17764072.

- ^ Friberg E, Wolk A (Jan 2009). "Long-term alcohol consumption and risk of endometrial cancer incidence: a prospective cohort study". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 18 (1): 355–8. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0993. PMID 19124521.

- ^ Moerman CJ, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB (1999). "The epidemiology of gallbladder cancer: lifestyle related risk factors and limited surgical possibilities for prevention". Hepatogastroenterology. 46 (27): 1533–9. PMID 10430290.

- ^ Ji J, Couto E, Hemminki K (September 2005). "Incidence differences for gallbladder cancer between occupational groups suggest an etiological role for alcohol". International Journal of Cancer. 116 (3): 492–3. doi:10.1002/ijc.21055. PMID 15800949.

- ^ Pandey M, Shukla VK (August 2003). "Lifestyle, parity, menstrual and reproductive factors and risk of gallbladder cancer". European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 12 (4): 269–72. doi:10.1097/00008469-200308000-00005. PMID 12883378.

- ^ Yagyu K, Kikuchi S, Obata Y, et al. (February 2008). "Cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking and the risk of gallbladder cancer death: a prospective cohort study in Japan". International Journal of Cancer. 122 (4): 924–9. doi:10.1002/ijc.23159. PMID 17955487.

- ^ La Vecchia C, Negri E, Franceschi S, Parazzini F, Gentile A, Fasoli M (September 1992). "Alcohol and epithelial ovarian cancer". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 45 (9): 1025–30. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(92)90119-8. PMID 1432017.

- ^ a b Alcohol consumption and cancer risk Archived 23 December 2012 at Archive.today

- ^ Genkinger JM, Hunter DJ, Spiegelman D, et al. (March 2006). "Alcohol intake and ovarian cancer risk: a pooled analysis of 10 cohort studies". British Journal of Cancer. 94 (5): 757–62. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6603020. PMC 2361197. PMID 16495916.

- ^ Nutrition and Prostate Cancer

- ^ Bagnardi V, Blangiardo M, La Vecchia C, Corrao G (November 2001). "A meta-analysis of alcohol drinking and cancer risk". British Journal of Cancer. 85 (11): 1700–5. doi:10.1054/bjoc.2001.2140. PMC 2363992. PMID 11742491.

- ^ Platz EA, Leitzmann MF, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Giovannucci E (March 2004). "Alcohol intake, drinking patterns, and risk of prostate cancer in a large prospective cohort study". American Journal of Epidemiology. 159 (5): 444–53. doi:10.1093/aje/kwh062. PMID 14977640.

- ^ a b Sesso HD, Paffenbarger RS, Lee IM (August 2001). "Alcohol consumption and risk of prostate cancer: The Harvard Alumni Health Study". International Journal of Epidemiology. 30 (4): 749–55. doi:10.1093/ije/30.4.749. PMID 11511598.

- ^ a b Schoonen WM, Salinas CA, Kiemeney LA, Stanford JL (January 2005). "Alcohol consumption and risk of prostate cancer in middle-aged men". International Journal of Cancer. 113 (1): 133–40. doi:10.1002/ijc.20528. PMID 15386436.

- ^ Cancer Research UK Prostate Cancer risk factors

- ^ Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center press release A Glass of Red Wine a Day May Keep Prostate Cancer Away

- ^ Middleton Fillmore K, Chikritzhs T, Stockwell T, Bostrom A, Pascal R (February 2009). "Alcohol use and prostate cancer: a meta-analysis". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 53 (2): 240–55. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200800122. PMID 19156715.

- ^ "Study links alcohol, prostate cancer". ABC News. 14 March 2009. Archived from the original on 20 June 2009. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ Chen CC, Neugut AI, Rotterdam H (1 April 1994). "Risk factors for adenocarcinomas and malignant carcinoids of the small intestine: preliminary findings". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 3 (3): 205–7. PMID 8019367.

- ^ Wu AH, Yu MC, Mack TM (March 1997). "Smoking, alcohol use, dietary factors and risk of small intestinal adenocarcinoma". International Journal of Cancer. 70 (5): 512–7. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970304)70:5<512::AID-IJC4>3.0.CO;2-0. PMID 9052748.

- ^ Negri E, Bosetti C, La Vecchia C, Fioretti F, Conti E, Franceschi S (July 1999). "Risk factors for adenocarcinoma of the small intestine". International Journal of Cancer. 82 (2): 171–4. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990719)82:2<171::AID-IJC3>3.0.CO;2-T. PMID 10389747.

- ^ Infante-Rivard C, El-Zein M (2007). "Parental alcohol consumption and childhood cancers: a review". J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 10 (1–2): 101–29. doi:10.1080/10937400601034597. PMID 18074306.

- ^ a b c Malcolm A. Smith, Lynn A. Gloeckler Ries, James G. Gurney, Julie A. Ross [3] National Cancer Institute 34 SEER Pediatric Monograph

- ^ a b c Gorini G, Stagnaro E, Fontana V, et al. (March 2007). "Alcohol consumption and risk of leukemia: A multicenter case-control study". Leukemia Research. 31 (3): 379–86. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2006.07.002. PMID 16919329.

- ^ Shu XO, Ross JA, Pendergrass TW, Reaman GH, Lampkin B, Robison LL (January 1996). "Parental alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and risk of infant leukemia: a Childrens Cancer Group study". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 88 (1): 24–31. doi:10.1093/jnci/88.1.24. PMID 8847721.

- ^ van Duijn CM, van Steensel-Moll HA, Coebergh JW, van Zanen GE (1 September 1994). "Risk factors for childhood acute non-lymphocytic leukemia: an association with maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy?". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 3 (6): 457–60. PMID 8000294.

- ^ Oleske D, Golomb HM, Farber MD, Levy PS (May 1985). "A case-control inquiry into the etiology of hairy cell leukemia". American Journal of Epidemiology. 121 (5): 675–83. doi:10.1093/aje/121.5.675. PMID 4014159.

- ^ Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV (December 2007). "Epidemiology of the plasma-cell disorders". Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 20 (4): 637–64. doi:10.1016/j.beha.2007.08.001. PMID 18070711.

- ^ a b Gorini G, Stagnaro E, Fontana V, et al. (January 2007). "Alcohol consumption and risk of Hodgkin's lymphoma and multiple myeloma: a multicentre case-control study". Annals of Oncology. 18 (1): 143–8. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdl352. PMID 17047000.

- ^ a b c d Ye W, Lagergren J, Weiderpass E, Nyrén O, Adami HO, Ekbom A (August 2002). "Alcohol abuse and the risk of pancreatic cancer". Gut. 51 (2): 236–9. doi:10.1136/gut.51.2.236. PMC 1773298. PMID 12117886.

- ^ a b c d Silverman DT, Brown LM, Hoover RN, et al. (1 November 1995). "Alcohol and pancreatic cancer in blacks and whites in the United States". Cancer Research. 55 (21): 4899–905. PMID 7585527.

- ^ a b c d Michaud DS, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Fuchs CS (1 May 2001). "Coffee and alcohol consumption and the risk of pancreatic cancer in two prospective United States cohorts". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 10 (5): 429–37. PMID 11352851.

- ^ Villeneuve PJ, Johnson KC, Hanley AJ, Mao Y (February 2000). "Alcohol, tobacco and coffee consumption and the risk of pancreatic cancer: results from the Canadian Enhanced Surveillance System case-control project. Canadian Cancer Registries Epidemiology Research Group". European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 9 (1): 49–58. doi:10.1097/00008469-200002000-00007. PMID 10777010.

- ^ a b Cancer Research UK Pancreatic cancer risks and causes

- ^ Ahlgren JD (April 1996). "Epidemiology and risk factors in pancreatic cancer". Seminars in Oncology. 23 (2): 241–50. PMID 8623060.

- ^ Cuzick J, Babiker AG (March 1989). "Pancreatic cancer, alcohol, diabetes mellitus and gall-bladder disease". International Journal of Cancer. 43 (3): 415–21. doi:10.1002/ijc.2910430312. PMID 2925272.

- ^ Harnack LJ, Anderson KE, Zheng W, Folsom AR, Sellers TA, Kushi LH (December 1997). "Smoking, alcohol, coffee, and tea intake and incidence of cancer of the exocrine pancreas: the Iowa Women's Health Study". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 6 (12): 1081–6. PMID 9419407.

- ^ Schottenfeld, D. and J. Fraumeni, ed. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. 2nd ed., ed. Vol。 1996, Oxford University Press: Oxford[page needed]

- ^ Olsen GW, Mandel JS, Gibson RW, Wattenberg LW, Schuman LM (August 1989). "A case-control study of pancreatic cancer and cigarettes, alcohol, coffee and diet". American Journal of Public Health. 79 (8): 1016–9. doi:10.2105/AJPH.79.8.1016. PMC 1349898. PMID 2751016.

- ^ "Pancreatic cancer risk factors". Info.cancerresearchuk.org. 2008-11-04. Retrieved 2009-09-15.

- ^ a b c "In summary, a weak positive association between alcohol intake during adulthood and pancreatic cancer risk was observed in the highest category of intake (≥30g/day or approximately 2 alcoholic beverages/day). Associations with alcohol intake were stronger among individuals who were normal weight. Thus, our findings are consistent with a modest increase in risk of pancreatic cancer for alcohol intakes of at least 30 grams/day." Genkinger JM, Spiegelman D, Anderson KE, Bergkvist L, Bernstein L, van den Brandt PA, English DR, Freudenheim JL, Fuchs CS, Giles GG, Giovannucci E, Hankinson SE, Horn-Ross PL, Leitzmann M, Männistö S, Marshall JR, McCullough ML, Miller AB, Reding DJ, Robien K, Rohan TE, Schatzkin A, Stevens VL, Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Verhage BA, Wolk A, Ziegler RG, Smith-Warner SA (March 2009). "Alcohol intake and pancreatic cancer risk: a pooled analysis of fourteen cohort studies". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 18 (3): 765–76. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0880. PMC 2715951. PMID 19258474.

- ^ Zatonski WA, Boyle P, Przewozniak K, Maisonneuve P, Drosik K, Walker AM (February 1993). "Cigarette smoking, alcohol, tea and coffee consumption and pancreas cancer risk: a case-control study from Opole, Poland". International Journal of Cancer. 53 (4): 601–7. doi:10.1002/ijc.2910530413. PMID 8436433.

- ^ Durbec JP, Chevillotte G, Bidart JM, Berthezene P, Sarles H (April 1983). "Diet, alcohol, tobacco and risk of cancer of the pancreas: a case-control study". British Journal of Cancer. 47 (4): 463–70. doi:10.1038/bjc.1983.75. PMC 2011343. PMID 6849792.

- ^ Bueno de Mesquita HB, Maisonneuve P, Moerman CJ, Runia S, Boyle P (February 1992). "Lifetime consumption of alcoholic beverages, tea and coffee and exocrine carcinoma of the pancreas: a population-based case-control study in The Netherlands". International Journal of Cancer. 50 (4): 514–22. doi:10.1002/ijc.2910500403. PMID 1537615.

- ^ Harnack LJ, Anderson KE, Zheng W, Folsom AR, Sellers TA, Kushi LH (1 December 1997). "Smoking, alcohol, coffee, and tea intake and incidence of cancer of the exocrine pancreas: the Iowa Women's Health Study". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 6 (12): 1081–6. PMID 9419407.

- ^ Durbec JP, Chevillotte G, Bidart JM, Berthezene P, Sarles H (April 1983). "Diet, alcohol, tobacco and risk of cancer of the pancreas: a case-control study". British Journal of Cancer. 47 (4): 463–70. doi:10.1038/bjc.1983.75. PMC 2011343. PMID 6849792.

- ^ Bueno de Mesquita HB, Maisonneuve P, Moerman CJ, Runia S, Boyle P (February 1992). "Lifetime consumption of alcoholic beverages, tea and coffee and exocrine carcinoma of the pancreas: a population-based case-control study in The Netherlands". International Journal of Cancer. 50 (4): 514–22. doi:10.1002/ijc.2910500403. PMID 1537615.

- ^ Villeneuve PJ, Johnson KC, Hanley AJ, Mao Y (February 2000). "Alcohol, tobacco and coffee consumption and the risk of pancreatic cancer: results from the Canadian Enhanced Surveillance System case-control project. Canadian Cancer Registries Epidemiology Research Group". European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 9 (1): 49–58. doi:10.1097/00008469-200002000-00007. PMID 10777010.

- ^ Genkinger JM, Spiegelman D, Anderson KE, et al. (March 2009). "ALCOHOL INTAKE AND PANCREATIC CANCER RISK: A POOLED ANALYSIS OF FOURTEEN COHORT STUDIES". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 18 (3): 765–76. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0880. PMC 2715951. PMID 19258474.

- ^ Kuijten RR, Bunin GR, Nass CC, Meadows AT (1 May 1990). "Gestational and familial risk factors for childhood astrocytoma: results of a case-control study" (PDF). Cancer Research. 50 (9): 2608–12. PMID 2328486.

- ^ Ben-Menachem T (August 2007). "Risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma". Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 19 (8): 615–7. doi:10.1097/MEG.0b013e328224b935. PMID 17625428.

- ^ Pelucchi C, La Vecchia C (February 2009). "Alcohol, coffee, and bladder cancer risk: a review of epidemiological studies". Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 18 (1): 62–8. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32830c8d44. PMID 19077567.

- ^ a b c Weiderpass E, Ye W, Tamimi R, et al. (1 August 2001). "Alcoholism and risk for cancer of the cervix uteri, vagina, and vulva". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 10 (8): 899–901. PMID 11489758.

- ^ Claus EB, Stowe M, Carter D (December 2001). "Breast carcinoma in situ: risk factors and screening patterns". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 93 (23): 1811–7. doi:10.1093/jnci/93.23.1811. PMID 11734598.

- ^ Kuijten RR, Bunin GR (1 May 1993). "Risk factors for childhood brain tumors". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2 (3): 277–88. PMID 8318881.

- ^ Howe GR, Burch JD, Chiarelli AM, Risch HA, Choi BC (1 August 1989). "An exploratory case-control study of brain tumors in children". Cancer Research. 49 (15): 4349–52. PMID 2743324.

- ^ Preston-Martin S, Yu MC, Benton B, Henderson BE (1 December 1982). "N-Nitroso compounds and childhood brain tumors: a case-control study". Cancer Research. 42 (12): 5240–5. PMID 7139628.

- ^ Stang A, Ahrens W, Anastassiou G, Jöckel KH (December 2003). "Phenotypical characteristics, lifestyle, social class and uveal melanoma". Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 10 (5): 293–302. doi:10.1076/opep.10.5.293.17319. PMID 14566630.

- ^ Chen L, Gallicchio L, Boyd-Lindsley K, et al. (2009). "Alcohol Consumption and the Risk of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: A Systematic Review". Nutr Cancer. 61 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1080/01635580802372633. PMC 3072894. PMID 19116871.

- ^ Heck JE, Ritz B, Hung RJ, Hashibe M, Boffetta P (March 2009). "The epidemiology of neuroblastoma: a review". Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 23 (2): 125–43. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.00983.x. PMID 19159399.

- ^ Actis AB, Eynard AR (November 2000). "Influence of environmental and nutritional factors on salivary gland tumorigenesis with a special reference to dietary lipids". Eur J Clin Nutr. 54 (11): 805–10. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601077. PMID 11114673.

- ^ van Hemelrijck; Mieke J.J. (2007). "Tobacco, Alcohol and Dietary Consumption: Behavior Risks Associated with Testicular Cancer?". Current Urology. 1 (2): 57–63. doi:10.1159/000106534.

- ^ Dal Maso L, Bosetti C, La Vecchia C, Franceschi S (February 2009). "Risk factors for thyroid cancer: an epidemiological review focused on nutritional factors". Cancer Causes Control. 20 (1): 75–86. doi:10.1007/s10552-008-9219-5. PMID 18766448.

- ^ Meinhold, C L; Park, Y; Stolzenberg-Solomon, R Z; Hollenbeck, A R; Schatzkin, A; Berrington De Gonzalez, A (2009). "Alcohol intake and risk of thyroid cancer in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study". British Journal of Cancer. 101 (9): 1630–4. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6605337. PMC 2778506. PMID 19862001.

- ^ Allen Naomi E., Beral Valerie, Casabonne Delphine, Sau, Kan Wan, Reeves Gillian K., Brown Anna, Green Jane (2009). "Moderate Alcohol Intake and Cancer Incidence in Women". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 101 (5): 296–305. doi:10.1093/jnci/djn514. PMID 19244173.CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ a b Madsen BS, Jensen HL, van den Brule AJ, Wohlfahrt J, Frisch M (June 2008). "Risk factors for invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva and vagina—population-based case-control study in Denmark". International Journal of Cancer. 122 (12): 2827–34. doi:10.1002/ijc.23446. PMID 18348142.

- ^ Parazzini F, Moroni S, Negri E, La Vecchia C, Dal Pino D, Cavalleri E (December 1995). "Selected food intake and risk of vulvar cancer". Cancer. 76 (11): 2291–6. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19951201)76:11<2291::AID-CNCR2820761117>3.0.CO;2-W. PMID 8635034.

- ^ Besson H, Brennan P, Becker N, et al. (August 2006). "Tobacco smoking, alcohol drinking and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: A European multicenter case-control study (Epilymph)". International Journal of Cancer. 119 (4): 901–8. doi:10.1002/ijc.21913. PMID 16557575.

- ^ Nieters A, Deeg E, Becker N (January 2006). "Tobacco and alcohol consumption and risk of lymphoma: results of a population-based case-control study in Germany". International Journal of Cancer. 118 (2): 422–30. doi:10.1002/ijc.21306. PMID 16080191.

- ^ Deandrea S, Bertuccio P, Chatenoud L, Franceschi S, Serraino D, La Vecchia C (June 2007). "Reply to 'Alcohol consumption and risk of Hodgkin's lymphoma and multiple myeloma: a multicentre case-control study' by Gorini et al". Annals of Oncology. 18 (6): 1119–21. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdm203. PMID 17586754.

- ^ Lee JE, Hunter DJ, Spiegelman D, et al. (May 2007). "Alcohol intake and renal cell cancer in a pooled analysis of 12 prospective studies". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 99 (10): 801–10. doi:10.1093/jnci/djk181. PMID 17505075.

- ^ Pelucchi C, Galeone C, Montella M, et al. (May 2008). "Alcohol consumption and renal cell cancer risk in two Italian case-control studies". Annals of Oncology. 19 (5): 1003–8. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdm590. PMID 18187482.

- ^ Rashidkhani B, Akesson A, Lindblad P, Wolk A (December 2005). "Alcohol consumption and risk of renal cell carcinoma: a prospective study of Swedish women". International Journal of Cancer. 117 (5): 848–53. doi:10.1002/ijc.21231. PMID 15957170.

- ^ Parker AS, Cerhan JR, Lynch CF, Ershow AG, Cantor KP (March 2002). "Gender, alcohol consumption, and renal cell carcinoma". American Journal of Epidemiology. 155 (5): 455–62. doi:10.1093/aje/155.5.455. PMID 11867357.

- ^ Pelucchi C, La Vecchia C, Negri E, Talamini R, Franceschi S (December 2002). "Alcohol drinking and renal cell carcinoma in women and men". European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 11 (6): 543–5. doi:10.1097/00008469-200212000-00006. PMID 12457106.

- ^ Mahabir S, Leitzmann MF, Virtanen MJ, et al. (1 January 2005). "Prospective study of alcohol drinking and renal cell cancer risk in a cohort of finnish male smokers". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 14 (1): 170–5. PMID 15668492.

- ^ Lee JE, Giovannucci E, Smith-Warner SA, Spiegelman D, Willett WC, Curhan GC (June 2006). "Total fluid intake and use of individual beverages and risk of renal cell cancer in two large cohorts". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 15 (6): 1204–11. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0889. PMID 16775182.

- ^ Setiawan VW, Stram DO, Nomura AM, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE (October 2007). "Risk factors for renal cell cancer: the multiethnic cohort". American Journal of Epidemiology. 166 (8): 932–40. doi:10.1093/aje/kwm170. PMID 17656615.

- ^ Morton LM, Zheng T, Holford TR, et al. (July 2005). "Alcohol consumption and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a pooled analysis". The Lancet Oncology. 6 (7): 469–76. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70214-X. PMID 15992695.

- ^ Lim U, Morton LM, Subar AF, et al. (September 2007). "Alcohol, smoking, and body size in relation to incident Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma risk". American Journal of Epidemiology. 166 (6): 697–708. doi:10.1093/aje/kwm122. PMID 17596266.

- ^ Lim U, Schenk M, Kelemen LE, et al. (November 2005). "Dietary determinants of one-carbon metabolism and the risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: NCI-SEER case-control study, 1998–2000". American Journal of Epidemiology. 162 (10): 953–64. doi:10.1093/aje/kwi310. PMID 16221809.

- ^ Briggs NC, Levine RS, Bobo LD, Haliburton WP, Brann EA, Hennekens CH (September 2002). "Wine drinking and risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma among men in the United States: a population-based case-control study". American Journal of Epidemiology. 156 (5): 454–62. doi:10.1093/aje/kwf058. PMID 12196315.

- ^ Besson H, Brennan P, Becker N, et al. (August 2006). "Tobacco smoking, alcohol drinking and Hodgkin's lymphoma: a European multi-centre case–control study (EPILYMPH)". British Journal of Cancer. 95 (3): 378–84. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6603229. PMC 2360649. PMID 16819547.

- ^ Chiu BC, Cerhan JR, Gapstur SM, et al. (July 1999). "Alcohol consumption and non-Hodgkin lymphoma in a cohort of older women". British Journal of Cancer. 80 (9): 1476–82. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6690547. PMC 2363074. PMID 10424754.

- ^ Patrick R. Hagner, Krystyna Mazan-Mamczarz, Bojie Dai, Sharon Corl, X. Frank Zhao, and Ronald B. Gartenhaus Alcohol consumption and decreased risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: role of mTOR dysfunction Blood28 May 2009, Vol. 113, No. 22, pp. 5526–5535. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-11-191783

- ^ Willett EV, Smith AG, Dovey GJ, Morgan GJ, Parker J, Roman E (October 2004). "Tobacco and alcohol consumption and the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma". Cancer Causes & Control. 15 (8): 771–80. doi:10.1023/B:CACO.0000043427.77739.60. PMID 15456990.

- ^ Chang ET, Smedby KE, Zhang SM, et al. (December 2004). "Alcohol intake and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in men and women". Cancer Causes & Control. 15 (10): 1067–76. doi:10.1007/s10552-004-2234-2. PMID 15801490.

- ^ Talamini R, Polesel J, Spina M, et al. (April 2008). "The impact of tobacco smoking and alcohol drinking on survival of patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma". International Journal of Cancer. 122 (7): 1624–9. doi:10.1002/ijc.23205. PMID 18059029.

- ^ Alcohol and Serious Consequences: Risks Increase Even With "Moderate" Intake Archived 20 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Corrao G, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, La Vecchia C (May 2004). "A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases". Preventive Medicine. 38 (5): 613–9. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.027. PMID 15066364.

- ^ World Cancer Research Fund, Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective, http://www.dietandcancerreport.org/

External links[edit]

- Other sites

- Science and medical sites

No comments:

Post a Comment